On Aug. 28, 1963, Bob Dylan was 22 years old and William Devereux Zantzinger was 24.

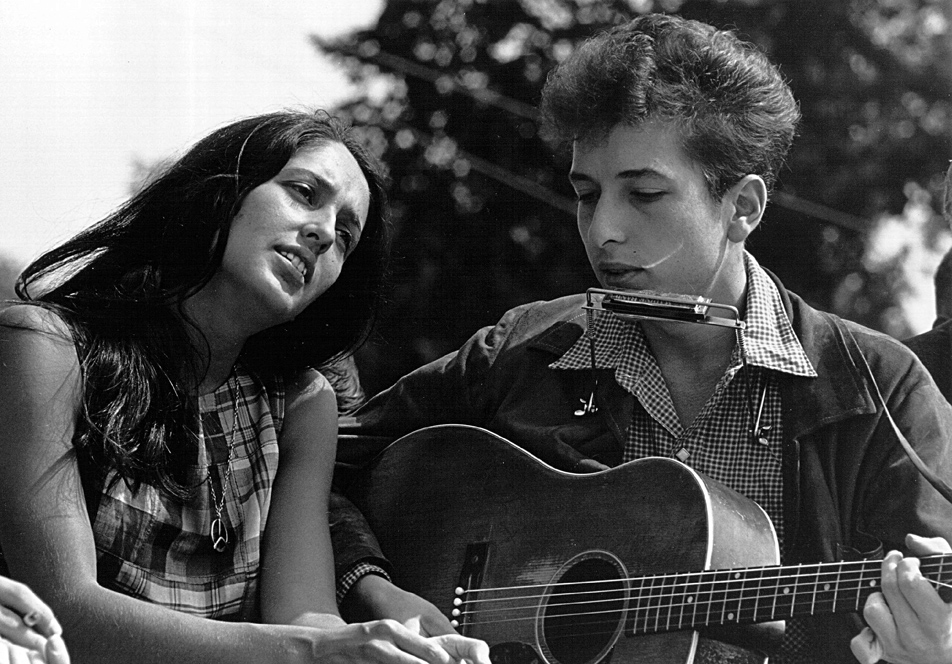

A folk singer from New York, Dylan performed at the civil rights march on Washington where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. At a courtroom 70 miles north in Hagerstown that same day, Zantzinger was sentenced in the death of an African-American barmaid.

Their two lives would soon intersect in ways that illuminate American history, and Hyattsville played a role.

The story begins on Feb. 8, 1963. Zantzinger, who managed his family’s 630-acre tobacco farm in Charles County in southern Maryland, went to a white-tie society ball in Baltimore with his wife. He was wearing a top hat and carrying a 25-cent wooden toy cane he had picked up at a carnival.

Zantzinger, who had already been denied service at a restaurant for being too rowdy, twirled the cane like Fred Astaire. As the night wore on, he hit several hotel employees with the cane and used racial epithets.

He then approached the bar and ordered a drink from Hattie Carroll, a 51-year-old who worked part-time at the Emerson Hotel. When she took too long, he struck her with the cane repeatedly, again using racial epithets. Carroll fled to the kitchen, where she told co-workers she felt “deathly ill.” An ambulance was called.

Zantzinger was charged with disorderly conduct and released on bail. But the next morning Carroll died of a stroke, and he was charged with murder.

In an interview as the trial started, Zantzinger made comments that led him to decide to avoid speaking with journalists ever again.

“Hell, you wouldn’t want to go to school with Negroes any more than you would with French people,” he said.

At the trial, which was moved to Hagerstown due to the publicity, Zantzinger testified that he didn’t remember hitting anyone. His lawyers argued that Carroll had other health problems that could have caused the stroke, and the charge was reduced to manslaughter. He was sentenced to a $500 fine and six months in the county jail—timed so that he could complete the tobacco harvest.

The UPI wire service ran a story, “Farmer Sentenced in Barmaid’s Death,” which was printed in the New York Times. A friend showed it to Dylan, who reportedly grew so incensed he stayed up all night writing a song about the case.

“William Zanzinger (sic) killed poor Hattie Carroll / With a cane that he twirled around his diamond ring finger /At a Baltimore hotel society gathering,” began “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” which appeared on his next album, the classic The Times They Are a-Changin’, released in January of 1964. Dylan got a few facts wrong, including the number of Carroll’s children, the spelling of Zantzinger’s name and his “high office relations in the politics of Maryland.”

In fact, his father, Richard Chew Zantzinger, was only a Republican state legislator for a single term in the 1930s. However, to Dylan’s larger point, his obituary notes that he was “prominent in Southern Maryland social circles,” founding two hunt clubs, belonging to the Society of the Cincinnati and serving on the state planning commission.

The Zantzingers’ prominence and wealth came in part from deals made in Prince George’s County, especially Hyattsville. Richard Zantzinger and his brother, Otway Jr., were real estate developers who worked a lot in the Hyattsville area with the firm O.B. Zantzinger Co. Otway Zantzinger subdivided the Hyattsville Hills neighborhood and built a number of homes in the historic district.

One of those homes, a brick bungalow at 4018 Hamilton St., was featured in this year’s Historic Hyattsville House Tour, which has tried to raise awareness of social issues in recent years. “[Otway] Zantzinger’s property deeds contain language that may not have raised eyebrows at the time, but today remind us of Hyattsville’s less than stellar history of racial exclusion—explicitly restricting residents of ‘Negro descent’ from owning the property—as well as prohibiting the making, selling and keeping of ‘spiritous liquors,'” the tour description notes.

These racial restrictions were once common throughout the United States. The land donated to become Magruder Park in 1927 even included a restriction noting that it was for white residents only, and all homes in University Park came with them. Though the Supreme Court ruled restrictive covenants based on race unconstitutional in 1948, they continued to be adhered to in private real estate sales and weren’t outlawed until the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Richard and Otway Zantzinger’s father, meantime, was also a real estate developer, whose biggest project was creating the Capitol Heights subdivision in 1904. As a history of that Prince George’s County community notes: “Advertisements noted that the segregated subdivision was intended for whites only.”

William Zantzinger, who died in 2009, declined to speak about the death of Hattie Carroll for years. But in a rare interview with Dylan biographer Howard Sounes, he called the future Nobel laureate a “no-account [expletive]” who had distorted the facts of the case.

“I should have sued him and put him in jail,” he said.

The Zantzingers’ restrictive covenants are now, thankfully, consigned to history, and today Hyattsville proudly cites its racial diversity as a strength. But “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” stands as a reminder of the not-so distant past.

Support the Wire and Community Journalism

Make a one-time donation or become a regular supporter here.

To add to the interesting, albeit distressing, information in this excellent post, the Zantzinger family, prior to purchasing their plantation in Charles County, lived in the Bonnie Brae estate in Hyattsville Hills. The house still exists — the last Victorian-era estate home remaining in Hyattsville — just north of the First Baptist Church at 42nd Ave. and Madison St. After the Zantzingers moved away, the mansion was a nursing home for about 50 years, then a home for abused women. It was sitting vacant when the church sold it a local builder, who conveyed it to another Hyattsville builder, who renovated it as a rental residential property several years ago. It is currently occupied by tenants.

Another historical footnote: The Hattie Carroll attack was not William Zantzinger’s only racially tinged run-in with the law. In more recent times, he owned some former sharecroppers’ hovels in southern Maryland, which he was renting out to African-American tenants. He wasn’t paying taxes on them, and eventually the properties were seized by the state. However, Zantzinger continued to manage and collect rent on the properties after he lost ownership of them, and he was finally arrested when the county government realized what was happening.

A final footnote: The Charles County plantation was sold by the Zantzingers to a German World Bank executive and his family. The man was the son of Claus von Stauffenberg, the German army officer who tried to assassinate Adolf Hitler. I stayed at the home a couple of times as a young man for weekend Catholic retreats, for which the family lent the home when they were staying in their D.C. home or in Germany.