Starting in the 1790s, enslaved people in Prince George’s County tried a novel way to gain their freedom: they took their owners to court.

The so-called “freedom suits” were much more common here than in other parts of the country and set legal precedents that are still cited today, according to historian William G. Thomas III, author of A Question of Freedom: The Families Who Challenged Slavery From the Nation’s Founding to the Civil War.

For Black History Month, he’ll be discussing Prince George’s County’s role in freedom suits in an online Profs and Pints lecture at 7 p.m. on Wednesday. You can also read more about the cases on his website about them.

Thomas talked with the Hyattsville Wire about why these cases were so prevalent here.

Why are you focused on Prince George’s County?

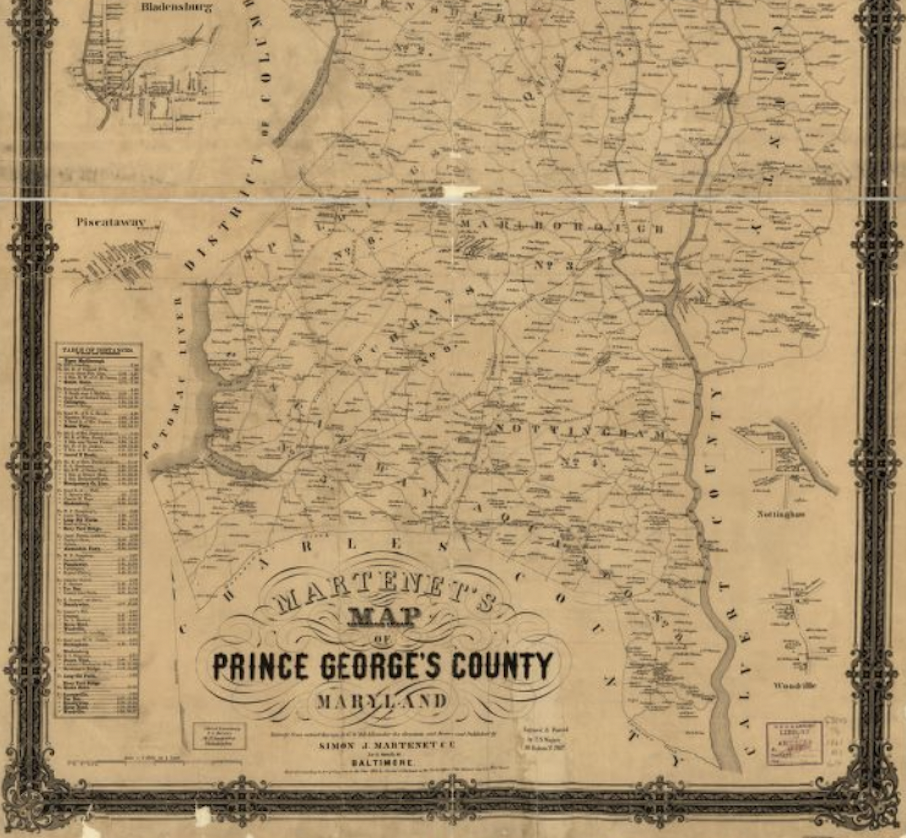

Some of the most important, early freedom suits originated in Prince George’s County in the 1790s. Several families, the Queens and Mahoneys, sued the Jesuits who had a plantation they called White Marsh. The site is on the Patuxent River, off Route 450. The bridge over the river used to be called “Priests Bridge.” Two of the most momentous freedom suits in American history began at White Marsh. And many of the lawyers, judges, and witnesses involved in these cases also came from Prince George’s County

Were there other factors?

Many enslaved men and women from Prince George’s were taken to Washington, D.C. Some were “hired out” or ordered to hire themselves out in the District. Some were separated from spouses in Prince George’s County and went back and forth. Forcing slaves to hire themselves out was a tactic by slaveholders in Prince George’s to continue to hold these people as property but to offload the costs by allowing the enslaved to keep their wages and pay for their own housing and food in the District. Simultaneously, enslaved men and women could use this degree of independence to accumulate resources to win eventual freedom, either by self-purchase or suing for freedom.

Ann Williams was from Bladensburg when she was sold in 1815 to a slave trader who planned to take her and her children to Georgia. Taken to a slave pen in D.C., she threw herself out of a third-floor window. Horribly injured, her case became widely known among antislavery residents of the District. There was a Congressional inquiry into the slave trade in D.C. and kidnapping. Eventually, seventeen years later she was living independently though still claimed as a slave by the slaveholder. She sued for freedom and the jury decided in her favor because she had lived for more than ten years on her own.

How did slavery in Prince George’s County compare to other parts of the country?

Slavery in Prince George’s County was extensive in the 1790s. More than 60 percent of the population of the county was enslaved. It was a place with a deep history of enslavement. White English colonists imported Black people from Africa in the transatlantic slave trade and commissioned slave ships to come into Annapolis. They grew tobacco over the 18th century and into the 19th century in Prince George’s County.

Slavery itself was little different from other parts of the country. Men, women, and children were held in bondage and treated as human property. They were bought and sold, separated, and mercilessly punished. Slavery was just as brutal in Prince George’s County as elsewhere.

What was different about the Chesapeake by the 1790s from other parts of the country and later periods was that there were Black families of three and four generations who had deep networks of kinship and belonging, especially in Prince George’s County. These families knew their own histories and ancestries. They had the resources to challenge their enslavement and access to the lawyers who might bring their lawsuits.

Why were these cases important?

The freedom suits in Prince George’s County were important because they challenged slavery using the law the slaveholders made. These lawsuits exposed slavery as a dubious institution in the law. And they showed that slavery had always been contested in English law, that there was no clear sanction for the concept of human property. In fact, the freedom suits were the most public and consequential form of resistance to the idea of slavery as a “property right” sanctioned by the Constitution, an idea that slaveholders relentlessly pursued to justify slavery.

The freedom suits sustained the concept of freedom as national, and slavery as something local and circumscribed in the law. The freedom suits from Prince George’s County were, perhaps, the deepest, longest line of antislavery constitutionalism.

Are there any other lasting effects of these cases?

One of the lasting effects is that many Black families in Maryland can trace their ancestry to the nation’s founding. And the history of their freedom can be found in communities they founded, like Queenstown and Duckettsville. Another is that the hearsay rule in Queen v. Hepburn is routinely cited today for better or worse. The decision rendered inadmissible much of the oral testimony that would have freed the Queens. The rule lives on in American law, but it’s worth pausing over. It came at the expense of a family’s freedom. What else do we take for granted, that if we knew its origins and meaning, we might question?

You can watch an interview with Thomas from December 2020 on the Prince Georges County Memorial Library System YouTube page here.