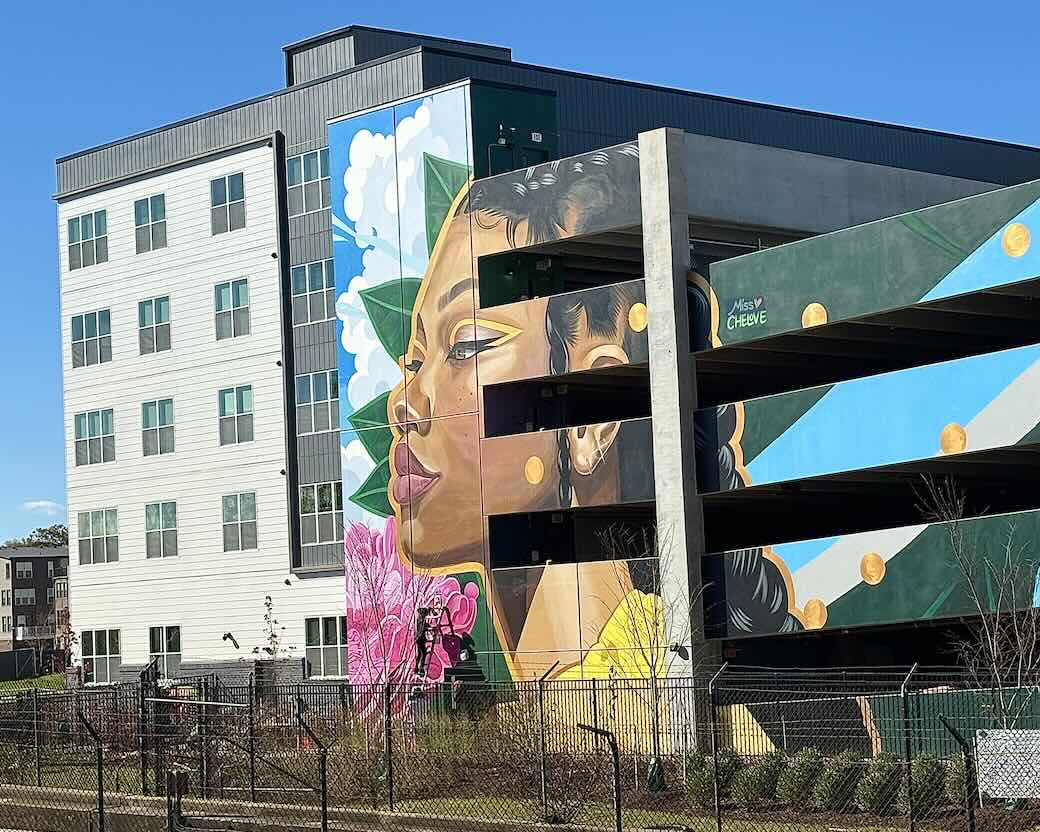

Charles Ball, who was once enslaved, is depicted heroically on the War of 1812 Bladensburg memorial, “Undaunted in Battle,” which is an 8 foot-by-10-foot bronze sculpture located near the Peace Cross at the intersection of Baltimore Avenue and Bladensburg Road.

Created by the late sculptor Joanna Campbell Blake, who worked out of a studio in Brentwood before her untimely death in 2016, the memorial depicts at its center Commodore Joshua Barney, who led a private military group made up of privateers, Chesapeake Bay watermen, merchant seamen, U.S. Navy sailors, freedmen and people who had escaped slavery.

Next to Barney, the Bladensburg memorial also depicts an unnamed Marine and Ball, who manned a cannon next to him throughout the battle, fighting until the very end.

Born into slavery in Calvert County around 1780, Ball was bought and sold several times before he escaped a particularly cruel family in Georgia in 1810 to reunite with his wife and children. He worked as a free man for various Maryland farmers before enlisting in the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla commanded by Barney.

African-Americans also fought on the British side in the battle, as the Royal Navy recruited enslaved men with the promise of freedom, and relocated them and their families to Nova Scotia and Bermuda after the war.

After the war, Ball’s wife died, and he remarried and bought a small farm of his own. Then, in 1830, a member of the Georgia family he had escaped tracked him down and had him kidnapped from his farm.

After two weeks in jail, Ball was taken in chains to Georgia, a trip which took him right through Bladensburg, as he later wrote:

On the evening of the second day, we halted at Bladensburg, and were shut up in a small house, within full view of the very ground, where sixteen years before I had fought in the ranks of the army, of the United States, in defence of the liberty and independence of that which I then regarded as my country. It seemed as if it had been but yesterday that I had seen the British columns, advancing across the bridge now before me, directing their fire against me, and my companions in arms.

The thought now struck me, that if I had deserted that day, and gone over to the enemies of the United States, how different would my situation at this moment have been. And this, thought I, is the reward of the part I bore in the dangers and fatigues of that disastrous battle.

Ball eventually escaped the Georgia plantation and made his way back to Maryland, where he learned that his wife and children had also been kidnapped and his farm taken over by a White man. With no legal ability to fight for his land and no way to find his family, he moved to Pennsylvania, where he wrote a memoir with the help of a White lawyer.

After the book was published in 1836, nothing more is known of Ball’s life, or the fate of his wife and children, but his memory lives on at the Bladensburg memorial.