J. Harris Rogers isn’t a household name, but he nearly was. For a brief period in the late 19th century, the Bladensburg inventor was a top rival to Alexander Graham Bell in the race to turn the telephone into a money-making business.

The son of an Episcopal preacher from Tennessee, Rogers became interested in the question of how to send audio over a wire while studying at Princeton.

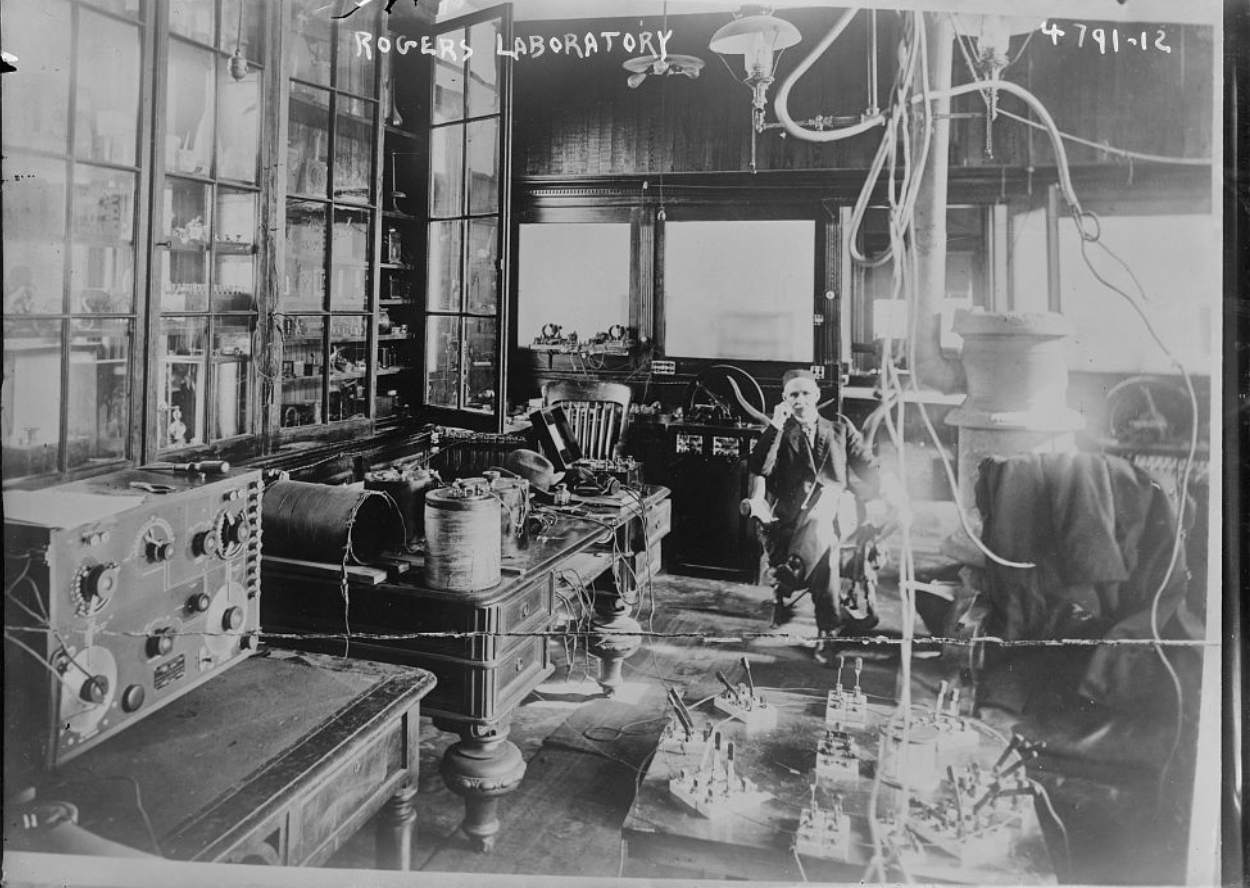

After graduation, he was appointed chief electrician of the U.S. Capitol building and continued his experiments on the side, filing several patents related to telephony.

Sensing an opportunity, his father, James Webb Rogers, bought a large house on a hill overlooking Bladensburg that he called the Parthenon to be used as a laboratory for his son’s experiments and started a business called the Pan-Electric Telephone Company.

The elder Rogers was a divisive figure, “variously described as a crank, an eccentric, a visionary, and a man of culture,” according to one historian. After his first attempt using money from Wall Street failed, he turned to his political contacts.

Tennessee Senator Isham Harris, a longtime friend of Rogers, was first to sign on. Various other political figures, including a former Confederate general, two former House members and members of President Grover Cleveland’s Cabinet soon joined in.

Rogers tried to recruit other members of Congress, too, even going so far as to send them letters and poems and show up at their offices.

The company, meantime, began organizing local phone companies using equipment built with designs from J. Harris Rogers’ patents, which in theory meant they weren’t running afoul of Bell’s wide-ranging patents for the phone. An electrician for Bell even said at one point that the Pan-Electric phone was a better design.

But Bell sued in Pennsylvania and won, and the threat of more lawsuits kept Pan-Electric from expanding into other states. Rogers convinced the Cleveland administration to launch its own lawsuit against Bell’s patents, which quickly became politicized.

The legal effort failed when the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Bell, and Rogers’ erratic political influence operation gave an unseemly air to the challenge, which was described by Cleveland’s opponents as a scandal.

Pan-Electric was dissolved in 1886, and “Ma Bell” went on to become the dominant telephone monopoly.

But during its long legal and political fight, Rogers and his son brought to light good evidence that Alexander Graham Bell’s patents were overly broad and his design derivative of other people’s inventions.

Their arguments that Bell was an unfair monopoly, meantime, eventually won out nearly a century later when a federal judge ordered the Bell system be broken up.

J. Harris Rogers’ went on to invent hundreds of other machines including one used for underwater communication by the Navy.

Support the Wire and Community Journalism

Make a one-time donation or become a regular supporter here.

This is great local history. It would be nice to see a post about the family’s subsequent history in the county, which was considerable. For example, J Harris Rogers went on to an illustrious career as a scientist and engineer, with many patents to his name. On the property of his Hyattsville mansion, Firwood (demolished to build the County Service Center), Harris built the only private lab that remained open throughout the First World War, and was visited by General Pershing himself. Harris invented underwater telegraphy, which was of keen interest to the US military during the Great War.

The Harris family were also known for being major developers of the Route 1 Corridor (many will recognize, for example, Rogers Heights, near Edmonston and Bladensburg). They were also major philanthropists, especially to Catholic institutions (the “Episcopal preacher” had converted to Catholicism prior to coming to Maryland, and J Harris Rogers was an active parishioner of St. Jerome’s in Hyattsville.

James Webb Rogers earned another footnote in American history when he welcomed the remnants of “Coxey’s Army” onto the grounds of The Parthenon and the LIttle Spa, after they had retreated from the US Capitol, where they stayed for some days and were ministered to by the pastor of St. Jerome’s Church.

The family seems to have mostly disappeared from the region, but there is a descendant who inherited and lives in Beall’s Pleasure in Lanham, one of the last of the historic Prince George’s County estates to remain in private hands.

Here in Rochester, NY, there is a Harris Radio corporation that makes special field communication radios for the Armed Forces. I know Harris is a common name, but given their inventions, I wonder if it could be a branch of the same family. I grew up in P.G. County and was told that my great-grandparents rented the Parthenon as a home in the early years of the 20th century. Coincidentally, their son, my grandfather, was also an electrician for the U.S. Capitol Building! He worked in what is called the Architect’s Office in the Capitol for 55 years, starting in the 1920s. I don’t know if the two families were connected, but there certainly seem to be a lot of coincidences here.

Beall’s Pleasure does remain standing and occupied amidst various industrial, commercial and residential development. I’d place the old estate in Landover, not Lanham, though I’ve heard Kentlands or even North Englewood as place names.

Actually the ZIP code for that part of the county (20785) is assigned to Hyattsville!