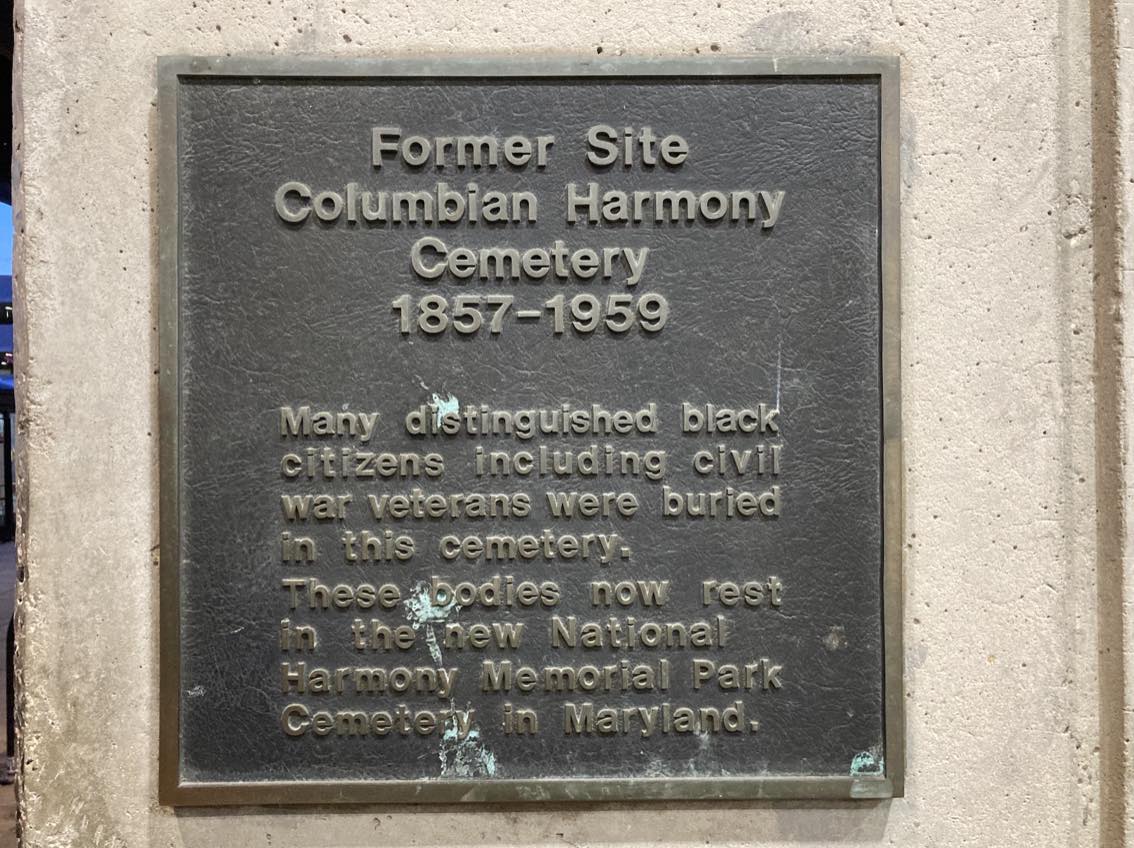

Just down Route 1 in D.C., a small plaque on a concrete column near the exit of the Rhode Island Avenue Metro station is all that’s left of the historic Columbian Harmony Cemetery, once the city’s most prominent African-American cemetery.

But the plaque does not tell the whole story.

“Many distinguished black citizens including civil war veterans were buried in this cemetery,” it reads. “These bodies now rest in the new National Harmony Memorial Park Cemetery in Maryland.”

The Metro station, which is now surrounded by apartments and shops, is gaining new attention for a bar opening soon in a renovated Metro car parked on site.

But the tragic backstory of the land beneath the Metro station is not as widely known.

The Columbian Harmony Cemetery was founded in 1857 by a mutual aid society founded by free African Americans after D.C. began cracking down on cemeteries inside what was then the urban center.

The new location was bounded by railroad tracks to the west, Rhode Island Avenue to the north, Brentwood Road NE to the east and T Street NE to the south.

For the first few years, the Columbian Harmony Society was busy carefully moving graves at its own expense from its old cemetery in Shaw. Among the first new burials at the new site were 452 Black and White Union soldiers killed in the Civil War.

By the 1880s, Columbian Harmony had become the most prominent African-American cemetery in D.C. Among those buried there were abolitionist Mary Ann Shadd Cary, the first Black woman to attend law school in the U.S.; Osborne Perry Anderson, the only African-American survivor of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry; Elizabeth Keckley, a former slave who was a civil rights activist and author and became a seamstress and confidante of First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln; and Philip Reid, the foundryman who oversaw the casting of the Statue of Freedom atop the Capitol. (You can read a list of other notable people who were interred here.)

In 1950, the cemetery stopped accepting new burials, and the Columbian Harmony Society struggled to afford the annual upkeep. A real-estate investor named Lewis N. Bell offered to buy the land and relocate the graves to what is now known as National Harmony Memorial Park at 7101 Sheriff Rd. in Landover, Md.

As it turned out, an unknown number of headstones and bodies that were supposed to be moved decades ago were not. Instead, the headstones were dumped unceremoniously on the banks of the Potomac River, used as riprap to prevent erosion, while workers found human remains when digging on the site in the 1970s. A larger planned memorial was never built.

While the original cemetery relocation took several years, Bell sought to move some 37,000 graves in just over six months beginning in May of 1960 — meaning hundreds had to be moved each day — in what was the largest cemetery relocation in D.C. ever. None of the ornate headstones or monuments were moved, and, by many accounts, many of the remains were not matched to the new, simple grave markers. This was unfortunately an all too common story of historic African-American cemeteries in the U.S. (You can watch a powerful news story here about this on CBS News which ran earlier this year.)

The city bought the land from Bell in 1967 with plans to build a highway that were later scrapped, and sold a portion to the Washington Metropolitan Transit Authority in 1974. While building the Metro station in 1976, WMATA workers found at least five coffins and other human remains, and city workers digging for a parking lot in 1979 found more pieces of cloth, coffin fragments and bones.

In 2009, kayakers in Virginia discovered that the old headstones and other grave markers had been used to line the river on a former plantation along the Potomac, and they are now being carefully excavated and moved to the Landover cemetery.

At different times, the city considered building a memorial near the Rhode Island Avenue Metro station, with 13 trees to represent the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery, benches and a dedication marker, but those never came to fruition. Instead, in 1981, the city put up a small plaque near the exit of the Metro, where it serves as the only reminder of the past.

You can learn more about the project to move the headstones here and donate to support the effort here.

Support the Wire and Community Journalism

Make a one-time donation or become a regular supporter here.